Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings | Ken Williams

The Sierra Adventure: The Story of Sierra On-Line | Shawn Mills

The Art of Point-and-Click Adventure Games | Bitmap Books

As I’ve mentioned previously, when I think back to my childhood, two images come to mind – riding my bike around the endless suburban streets of western Sydney, and playing computer games as much as I was allowed. Name a PC game from 1983 to around 1998 and chances are I’ve played it. From Commander Keen to Command and Conquer; Castle Adventure, Descent, Prince of Persia, Scorched Earth, Eye of the Beholder, Lemmings, Supaplex, JetPack, Earthsiege, Alone in the Dark. The list goes on.

But most of all I loved Sierra games. In the 80s and early 90s, Sierra On-Line dominated the PC gaming market. I loved them so much that I had dreams of one day working there. But in the late 90s, as the company deteriorated and eventually closed down, so too my interest in gaming dwindled.

At this time, every other game seemed to be another shooter with little-to-no story nor characters with whom to interact. Funnily enough, one of the last Sierra-published-games I got into was Half Life (which I loved). But mostly all I saw was a sea of sameness and as such I switched my attention to teaching myself 3D animation, website design and coding – all of which revolved around making fan content for my favourite series Space Quest. My goal switched from playing to creating.

Two books (the first two listed above) have been released in the last few months which have given some insight into the history of Sierra On-Line – how it began, how it thrived, and how it spectacularly fell apart. I devoured both books in only a couple of sessions.

At 8 years of age I tried to win over girls as Larry

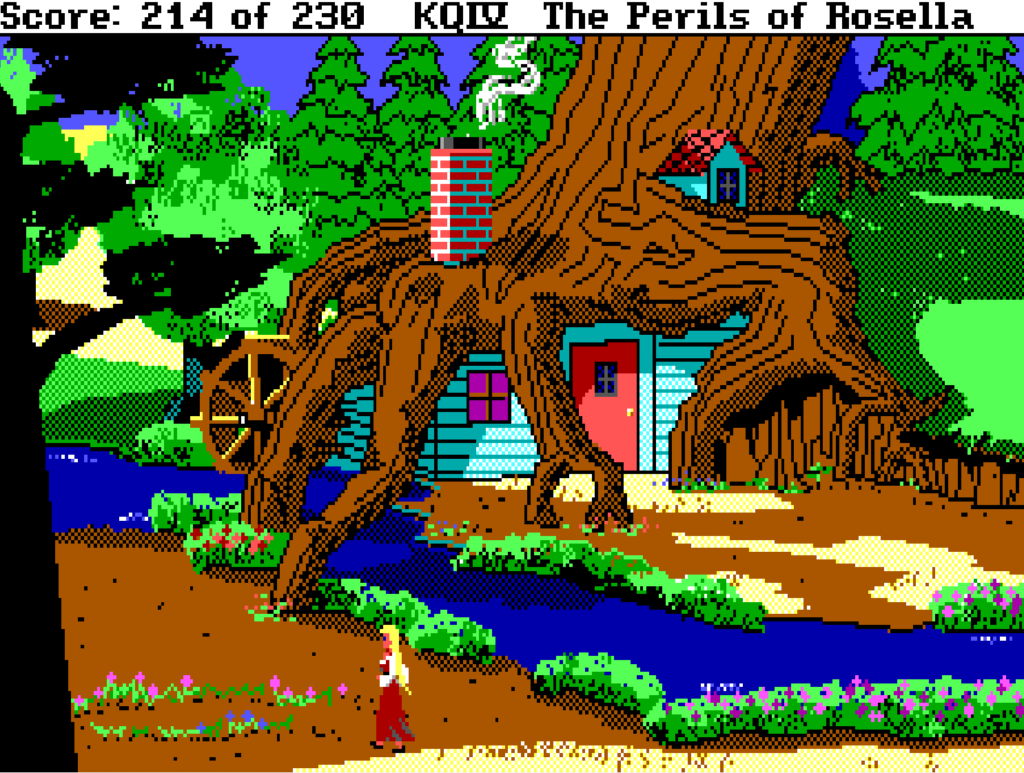

King’s Quest was always their crown

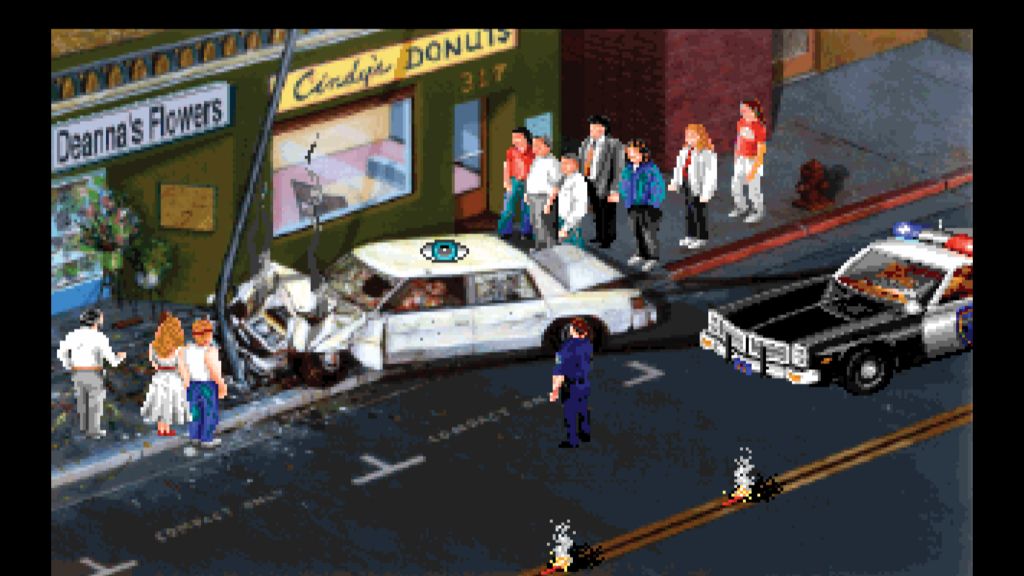

Police Quest keeping it gritty

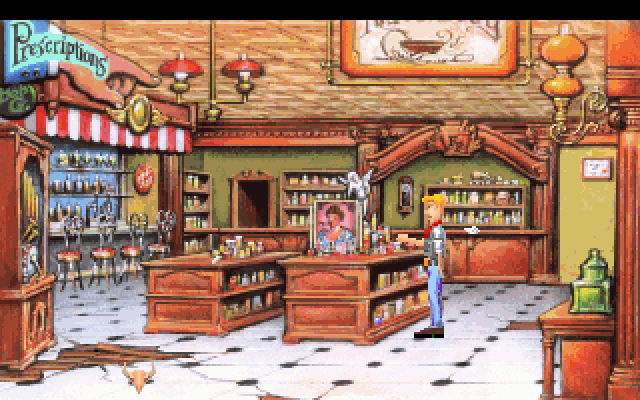

Freddy Pharkas Frontier Pharmacist

Space Quest. There’s nothing like it.

The Sierra Adventure is a work of love, written by a fan with the backing of a number of other fans via Kickstarter. It chronicles the company from its early days to its unfortunate end, highlighting the key games, designers and technologies along the way. Sierra’s success was found in its designer-driven approach and its technological boundary-pushing. No great work of art is designed by committee. As a Sierra fan, you always felt like part of a club or family, and got to know the game designers in the same way you would the author of a book. In the early days you could even call the designer to talk to them directly when you got stuck.

Unfortunately this approach was also expensive. An adventure game requires, story, dialogue, and characters. A successful game would sell around 250,000 copies and require a budget of around a quarter of the expected revenue. By the mid-nineties these numbers just weren’t competitive. Shawn Mills says it best:

A cultural change occurred in the early nineties that saw computers become a staple in most homes. They were no longer just for the tech-savvy, and as more and more people began using them throughout the decade, games and software were simplified to reach a broader audience.

More importantly, the technological advancement to 3D would become one of the major downfalls of the point-and-click adventure. While fast-paced, action-oriented games increased in popularity, the more cerebral adventure genre no longer dominated the market.

Shawn Mills, The Sierra Adventure

Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings – written by Sierra’s co-founder and CEO for most of the company’s life, Ken Williams – covers similar ground from the perspective of the ultimate insider. It’s far more business-oriented, which becomes fascinating when considering what led to both the successes and failures of the company.

A few highlights:

- Sierra made an offer to purchase id Software following the release of Wolfenstein 3D, which failed mostly due to stubbornness. Pride can be a bitch. Imagine the future which might have followed.

- Ken Williams was adamant about games being driven by the singular vision of an individual designer – a belief I strongly agree with for any decent creative endeavour (“if you were to take the two greatest book authors in the world and have them collaborate on a book, the result would not be as strong as their producing two independent books“). When new management took over, they used numbers and spreadsheets to assign people to projects. Original game designers were placed on games for which they had no passion while others were placed in charge of their original creation with little to no understanding of the world which had been created over fifteen years.

- Sierra (and Microsoft) benefited from IBM’s fear of government anti-trust laws. IBM wrote into their contracts that each company must make their product available elsewhere. As such, when IBM caught a cold it hit them harder and allowed Sierra to sail off with other manufacturers.

- The concept of a game “engine” which could be repurposed for new games without having to be coded from the ground up was pioneered by Sierra’s SCI. It’s what allowed them to push out ten times more titles than their competitors. It was also amusing the see the parallels with my own experience in the VFX industry as creatives would become frustrated with updates under the hood.

- It struck me how much the experience of working in the gaming industry at that time lines up with my own experience working in the film industry. Bill Gates is paraphrased in the book: “when you are in a business that depends entirely on having a series of hits, it’s just a matter of time until you fail“.

Invariably, in a company that grows the way Sierra grew, innovation gives way to emulation. Whereas Sierra’s management once strove to make it solid, profitable, and yet fun, they now strive to dominate other companies, force annual growth in the double digits, and (Like so many other companies) cut jobs mercilessly to improve the bottom line and thrill the stockholders.

Josh Mandel, echoing a sentiment true of any company

Not All Fairy Tales was written thanks to Ken being trapped indoors during the pandemic. In a similar way, my desire to explore again the possibility of creating my own game has risen with all the time I’ve had stuck indoors this year. I’ve been learning Unreal Engine and making my own digital art again and my mind has exploded with ideas of how one might tackle an adventure game in 2020. I’ll save that for another time.